Scarring alopecias encompass several medical conditions that destroy hair follicles and replace them with scar tissue, causing permanent hair loss. Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is the most common type of scarring alopecia in adults.(1) LPP was first described in 1895 by Pringle as a subtype of lichen planus (a chronic, recurrent rash caused by inflammation) that affects the hair follicles.(2) About 17-28% of people with LPP may also have lichen planus.(2) The cause of LPP is not well understood; there are theories that it is a hair specific autoimmune disorder that causes chronic inflammation.(1) It is a rare condition that mainly occurs in white women. The average age of onset is around 52 years, however cases have spanned from 16 to 76 years.(1,3) Less frequently it has also been reported in men with average age of onset of 36 years.(1) Additionally, it may also occur within families, suggesting a possible genetic link (4) and in children (5), although both of these scenarios are rare.

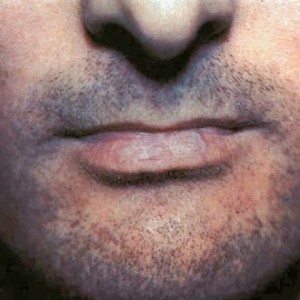

Symptoms of LPP may include scaly patches of hair loss randomly throughout the scalp or grouped hair loss in the centre and sides of the scalp, similar to the more well-known pattern baldness.(2) Additional areas, such as the eyebrows, arms, legs, and pubic area may also be affected.(1) Other common complaints involve itching, pain, and burning from the inflammation.

This pattern of hair loss may also mask or be confused with alopecia areata (an immune-related hair loss condition), especially in children.(5) Disease prognosis varies from gradual onset and spontaneous remission to a chronic condition, despite treatment.(1)

The treatment goal for LPP is to stop the progression of the lesions. Therapy generally entails topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antibiotics, and anti-malarials initially and can be increased to immunosuppressant drugs.(6) Further studies have also reported the use of thalidomide, antifungals, and minoxidil, all with varying effects.(2) Please talk to your physician or hair loss expert for diagnosis and individual treatment recommendations.

Article by: M.A. MacLeod, MSc., Mediprobe Research Inc.

References

- Lyakhovitsky A, Amichai B, Sizopoulou C, Barzilai A. A case series of 46 patients with lichen planopilaris: Demographics, clinical evaluation, and treatment experience. J Dermatol Treat. 2015 Jun;26(3):275–9.

- Soares VC, Mulinari-Brenner F, Souza TE de. Lichen planopilaris epidemiology: a retrospective study of 80 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2015 Oct;90(5):666–70.

- Tandon YK, Somani N, Cevasco NC, Bergfeld WF. A histologic review of 27 patients with lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Jul;59(1):91–8.

- Misiak-Galazka M, Olszewska M, Rudnicka L. Lichen planopilaris in three generations: grandmother, mother, and daughter – a genetic link? Int J Dermatol. 2015 Dec 23;

- Christensen KN, Lehman JS, Tollefson MM. Pediatric Lichen Planopilaris: Clinicopathologic Study of Four New Cases and a Review of the Literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Oct;32(5):621–7.

- Spano F, Donovan JC. Efficacy of oral retinoids in treatment-resistant lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Nov;71(5):1016–8.