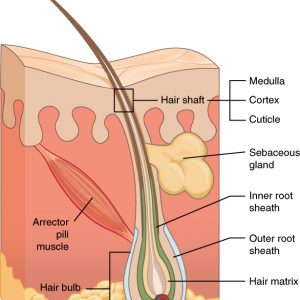

Trichorrhexis nodosa (TN) is a hair shaft disorder affecting all ethnicities1. Individuals with this disorder usually have fragile or easy to break hair due to cuticle loss (loss of the outer hair shaft layer)2. When the cuticle disappears, the exposed fibers separate and start to fray, looking a little like crushed paint brushes when magnified under the microscope3. This hair shaft disorder can lead to both diffuse or patchy hair loss due to the cuticle-less hair’s high susceptibility to fracture and breakage2.

Even though this condition can appear as early as birth (congenital TN), TN is more frequently developed later in life, as a result of hair styling habits. Frequent heat (blow drying or straightening), excessive brushing, chemical relaxation and even scratching can lead to acquired TN4–6. The chances of acquiring this disorder increases if you have a hair structure disorder or have medical conditions like a multisystem disorder (trichothiodystrophy), mental impairment, or abnormal thyroid levels (hypothyroidism)7–9. Curly hair is also easier to damage10–12.

Unsure whether or not you have TN? Individuals with TN usually have shorter hair that is uneven in length in areas more prone to repeated damage such as the top and back of the head4. You should be able to distinguish these shortened hairs from layered hair styles as they typically have blunter ends. The tug test can also be used to help identify this disorder. When a hair is gently tugged it will result in a broken hair fiber. An expert can then make a diagnosis based how this broken hair looks under a microscope3.

When treating TN the main goal is to protect the hair shaft and minimize further damage1. Disease progression can be reduced by limiting hair shaft trauma such as decreasing the amount of time blow drying or brushing your hair. Treatment can be difficult in cases where there are multiple diseases or conditions that co-occur with TN. In those suffering from additional conditions such as argininosuccinic aciduria (an ammonia disorder), specialized diets have been prescribed with some success13. In other conditions like hypothyroidism, daily doses of 0.1 mg L-thyroxine sodium for 6 months can help with TN9. In a case study of an individual with nail disease co-occurring with TN, 8 weeks of minoxidil therapy was able to resolve TN and lead to increased hair density and hair length14.

Maintaining a regular cleansing routine is important to remove styling aids, dirt, and dust and is a great first step to healthy hair15. Nonetheless, individuals with TN should avoid shampoos that contain anionic surfactants as they can make hair follicles more prone to breakage1,15. Non-ionic or amphoteric surfactants are better suited for hair shaft disorders as they are gentler and are more helpful in retaining moisture16. A Sure Hair representative can suggest which shampoo brands are ideal for you as product labels may not use these terms. Shampooing frequently also depends on your hair type and hair condition. Curly haired individuals should limit shampooing to once a week as a greater shampoo frequency might increase the risk of hair breakage17.

Conditioners are also recommended for hair shaft disorders. Conditioners can help prevent damage associated with daily grooming habits and can stop the progression of hair breakage18,19. Film-forming agents that are found in leave-in conditioners can help reduce static electricity, a cause of hair breakage1. Protein-containing conditioners could also strengthen your hair as they can help repair holes and defects within the hair shaft created by chemical or thermal styling techniques1,20.

If you have any questions in regards to your hair shaft disorder, speak with your hair transplant physician or specialist.

Article by: Sarah Versteeg MSc, Mediprobe Research Inc.

- Haskin A, Kwatra SG, Aguh C. Breaking the Cycle of Hair Breakage: Pearls for the Management of Acquired Trichorrhexis Nodosa. J Dermatol Treat. 2016 Oct 10;1–19.

- Whiting DA. Structural abnormalities of the hair shaft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987 Jan;16(1 Pt 1):1–25.

- Singh G, Miteva M. Prognosis and Management of Congenital Hair Shaft Disorders with Fragility-Part I. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Sep;33(5):473–80.

- Martin AM, Sugathan P. Localised acquired trichorrhexis nodosa of the scalp hair induced by a specific comb and combing habit – a report of three cases. Int J Trichology. 2011 Jan;3(1):34–7.

- Miyamoto M, Tsuboi R, Oh-I T. Case of acquired trichorrhexis nodosa: scanning electron microscopic observation. J Dermatol. 2009 Feb;36(2):109–10.

- Hwang ST, Park BC. Trichorrhexis nodosa after hair transplantation: dermoscopic, pathologic and electron microscopy analyses. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2013 Nov;39(11):1721–4.

- Rogers M. Hair shaft abnormalities: Part I. Australas J Dermatol. 1995 Nov;36(4):179–84; quiz 185–6.

- Rudnicka L, Rakowska A, Kerzeja M, Olszewska M. Hair shafts in trichoscopy: clues for diagnosis of hair and scalp diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Oct;31(4):695–708, x.

- Lurie R, Hodak E, Ginzburg A, David M. Trichorrhexis nodosa: a manifestation of hypothyroidism. Cutis. 1996 May;57(5):358–9.

- Khumalo NP. African hair length: the picture is clearer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 May;54(5):886–8.

- Tanus A, Oliveira CCC, Villarreal DJV, Sanchez FAV, Dias MFRG. Black women’s hair: the main scalp dermatoses and aesthetic practices in women of African ethnicity. An Bras Dermatol. 2015 Aug;90(4):450–65.

- Khumalo NP, Doe PT, Dawber RP, Ferguson DJ. What is normal black African hair? A light and scanning electron-microscopic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 Nov;43(5 Pt 1):814–20.

- Mirmirani P. Ceramic flat irons: improper use leading to acquired trichorrhexis nodosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Jan;62(1):145–7.

- Nagamani SCS, Erez A, Lee B. Argininosuccinate Lyase Deficiency. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJ, et al., editors. GeneReviews(®) [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993 [cited 2016 Oct 25]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51784/

- Harrison S, Sinclair R. Hypotrichosis and nail dysplasia: a novel hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Australas J Dermatol. 2004 May;45(2):103–5.

- Bouillon C. Shampoos and hair conditioners. Clin Dermatol. 1988 Sep;6(3):83–92.

- Crawford K, Hernandez C. A review of hair care products for black individuals. Cutis. 2014 Jun;93(6):289–93.

- Monselise A, Cohen D, Wanser R, Shapiro J. What ages hair? Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:161–6.

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Hair cosmetics: an overview. Int J Trichology. 2015 Mar;7(1):2–15.

- Bolduc C, Shapiro J. Hair care products: waving, straightening, conditioning, and coloring. Clin Dermatol. 2001 Aug;19(4):431–6.

- Draelos ZD. Shampoos, conditioners, and camouflage techniques. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Jan;31(1):173–8.